NMR - Circumscription

Nonmonotonic Reasoning

Circumscription is built on the principle of minimization. When we designate a set of predicates—such as Abnormal(x)—as minimized, the logic chooses models in which these predicates are made false as much as possible. Unless there is a compelling reason to assume an exception, Abnormal is set to 0. This reflects the guiding idea of circumscription: do not assume abnormalities unless forced to. As a result, in the absence of additional knowledge, the default inference that birds fly is preserved, because abnormal cases are minimized.

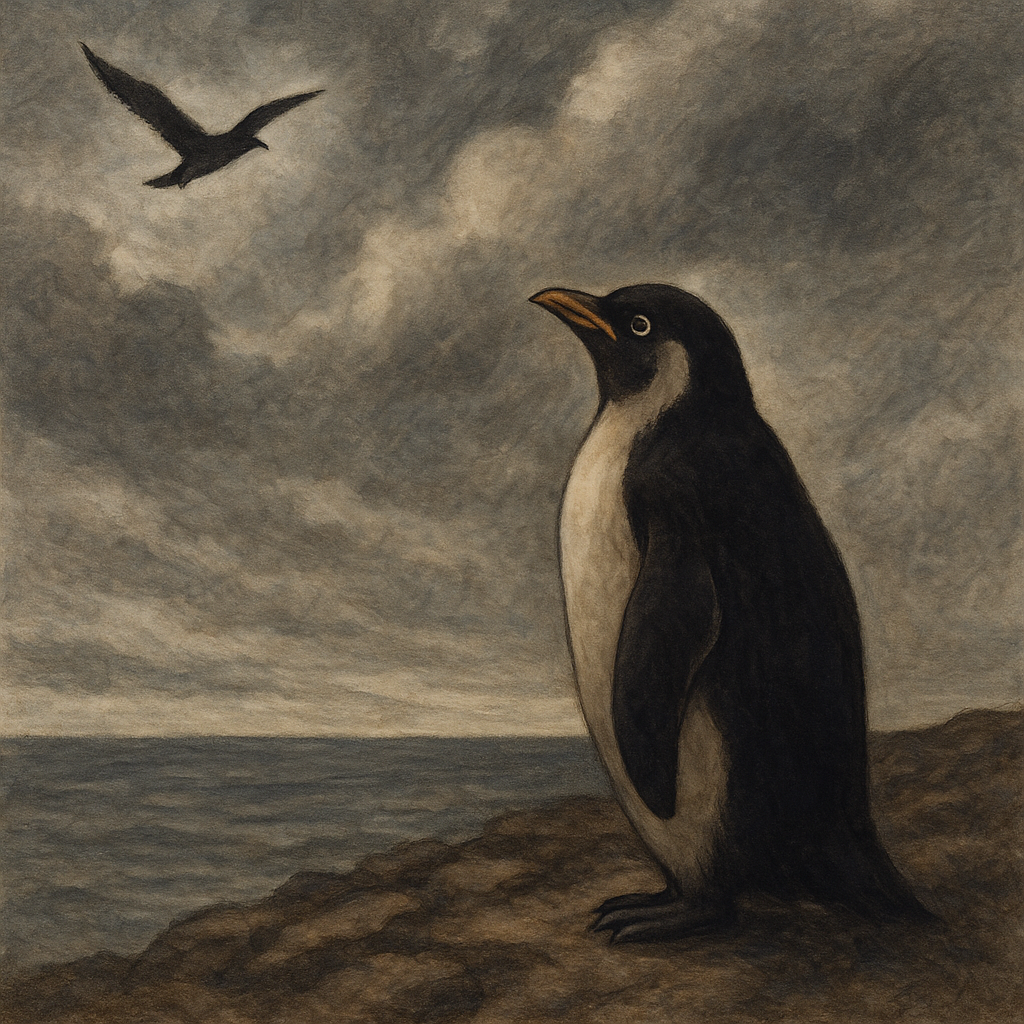

When new knowledge is introduced, the situation changes. Suppose we add the fact “Tweety is a penguin” together with the rule “penguins are abnormal.” In order to satisfy the underlying theory (\Gamma), every admissible model must now assign Abnormal(Tweety)=1. Circumscription still attempts to minimize Abnormal, but minimization cannot override the logical requirement imposed by the new information. The set of minimal models therefore shifts: models that previously set Abnormal(Tweety)=0 are no longer valid, and only those with Abnormal(Tweety)=1 remain.

This demonstrates the central mechanism of circumscription. It selects models that both satisfy the theory and minimize the chosen predicates. At first, the minimal models supported the conclusion that Tweety flies. After the penguin information is added, the minimal models change, and the conclusion flips to Tweety does not fly.

The overall effect is a form of reasoning that is non-monotonic. In classical monotonic logic, once a conclusion is derived, it remains valid even as more facts are added. In circumscription, by contrast, conclusions may be revised when new knowledge changes which models count as minimal. For this reason, circumscription is considered a framework for non-monotonic reasoning: conclusions can be withdrawn when new information forces additional exceptions into the minimal models.

r

Understanding Circumscription in Non-Monotonic Logic

Circumscription is a formal method introduced by John McCarthy (1980) to handle non-monotonic reasoning — situations where adding new knowledge can invalidate previous conclusions. It plays a key role in representing default assumptions and minimizing exceptions in logical systems.

Motivation

In classical (monotonic) logic, once something is derived, it remains true regardless of additional information. But this is often too rigid for real-world reasoning.

Example:

“Birds can fly.”

Later, we learn:

“Penguins are birds that cannot fly.”

This new information contradicts the previous generalization. To model such exceptions in a principled way, Circumscription allows us to minimize the abnormal or exceptional cases.

Basic Pattern: Using Abnormal Predicates

The most common approach introduces an auxiliary predicate like $\text{Abnormal}(x)$:

\[\text{Bird}(x) \land \neg \text{Abnormal}(x) \rightarrow \text{Flies}(x)\]Then we circumscribe (minimize) $\text{Abnormal}(x)$, assuming that most birds are not abnormal (i.e., can fly) unless specified otherwise.

Formal Definition of Circumscription

In the formal definition of circumscription:

\[\operatorname{Circ}(T; P) := T \land \forall P'\ \Big( \Big[ T[P \leftarrow P'] \land \forall x\ (P'(x) \rightarrow P(x)) \Big] \Rightarrow \forall x\ (P(x) \rightarrow P'(x)) \Big)\]the universal quantification over \(P'\) plays a central role in enforcing minimality of the predicate \(P\).

🔁 What Does “\(\forall P'\)” Mean?

The expression: $ \forall P’\ \Big( \cdots \Big) $ means we are considering all possible alternative interpretations \(P'\) of the predicate \(P\). We then compare our current interpretation of \(P\) with each \(P'\) that satisfies:

- \(T[P \leftarrow P']\): the theory \(T\) remains true when \(P\) is replaced with \(P'\)

- \(\forall x\ (P'(x) \rightarrow P(x))\): the interpretation \(P'\) is a subset of \(P\), i.e., \(P' \subseteq P\)

If such a smaller \(P'\) exists and still satisfies the theory, then we must have:

\[\forall x\ (P(x) \rightarrow P'(x))\]This implies:

\[P \subseteq P'\]Now, since we already assumed \(P' \subseteq P\), this gives us:

\[P = P'\]✅ Summary Interpretation

The entire implication:

\[\forall P'\ \Big( \Big[ T[P \leftarrow P'] \land P' \subseteq P \Big] \Rightarrow P = P' \Big)\]can be interpreted as:

“Among all possible alternative interpretations of \(P\), we only accept those in which no smaller \(P'\) can replace \(P\) without violating the theory. Hence, \(P\) must be minimal among all such candidates.”

📌 Why Is This Important?

This mechanism ensures that the predicate \(P\) (often something like \(\text{Abnormal}(x)\)) is assigned only when strictly necessary. Any non-minimal assignment of \(P\) would be invalidated by a smaller interpretation \(P'\) unless it’s logically unavoidable.

In model-theoretic terms, circumscription prunes the model space to those where the interpretation of \(P\) is minimal, given the constraints of the theory \(T\).

🧠 In Short

- \(\forall P'\) expresses a global comparison with all possible interpretations of \(P\)

- Circumscription accepts only those interpretations where \(P\) is the smallest possible set satisfying \(T\)

- This is what allows circumscription to represent default assumptions and minimize exceptions

Two Main Approaches to Circumscription

1. Using an Abnormal Predicate (Default Reasoning)

This is the standard approach:

\[\text{Bird}(x) \land \neg \text{Abnormal}(x) \rightarrow \text{Flies}(x)\]We circumscribe $\text{Abnormal}(x)$ to minimize exceptions. It reflects the idea that flying is the default for birds unless otherwise stated.

This approach is widely used in AI for:

- Default rules

- Expert systems

- Frame problem

2. Minimizing a Target Predicate Directly

Instead of introducing an auxiliary predicate, you can directly minimize an existing one.

Example:

\[\text{Bird}(x) \rightarrow \text{Flies}(x)\]Circumscribing $\text{Flies}(x)$ would force the set of flying birds to be as small as possible — which may contradict our intuition (e.g., most birds fly). Therefore, this approach is less commonly used unless you want to restrict the application of a predicate.

Note: Use with caution — it may produce unintuitive results.

Summary

| Approach | Predicate Minimized | Interpretation | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Using Abnormal(x) | $\text{Abnormal}(x)$ | Minimize exceptions | Default reasoning |

| Direct minimization | $\text{Flies}(x)$ (etc.) | Minimize application of a predicate | Restrictive modeling |

Conclusion

Circumscription gives us a powerful tool to represent “things are normally like this, unless otherwise stated” in a logically rigorous way. By deciding which predicate to minimize, we can fine-tune the inference behavior of intelligent systems.

References

Alviano, Query Answering in Propositional Circumscription, IJCAI, 2018

McCarthy, Applications of Circumscription to Formalizing Common Sense Knowledge, 1986

Bonatti, Description Logics with Circumscription, 2006

Walter Forkel, Revisiting Circumscription, 2017