Resource-rational analysis

Understanding human cognition as the optimal use of limited computational resources

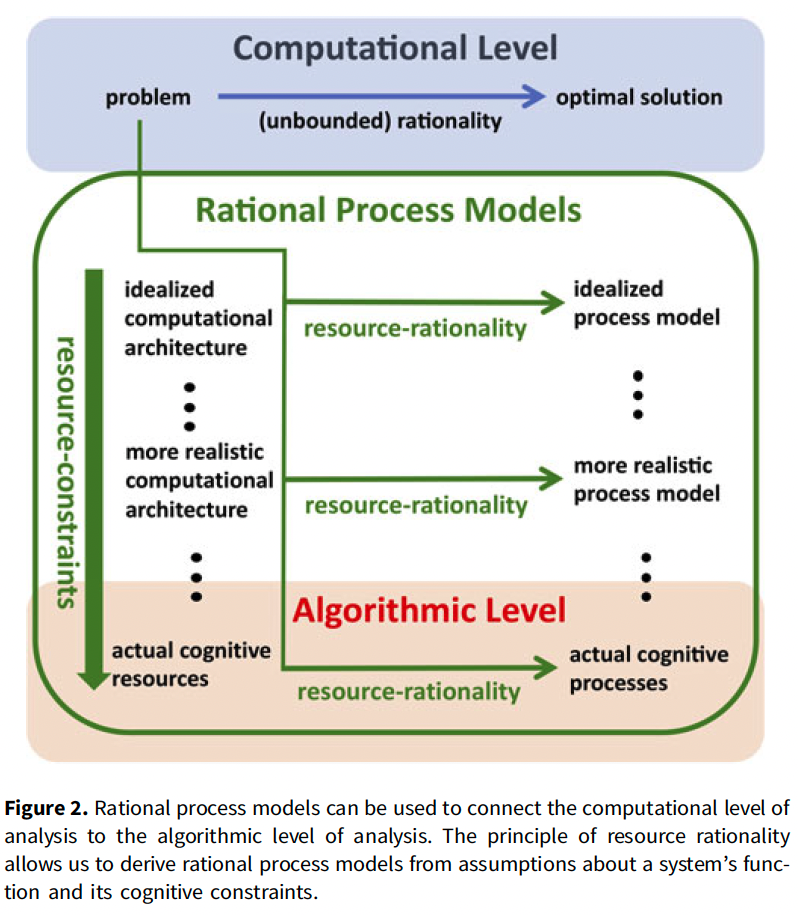

Integration of Bottom-Up and Top-Down Approaches in Cognitive Modeling

The integration of bottom-up cognitive constraints and top-down rational principles is emerging as a promising approach across multiple disciplines. Initial findings indicate that combining these strengths leads to more robust models capable of explaining a broader range of cognitive phenomena.

Key Applications:

- Economics: Development of mathematical models for bounded-rational decision-making to account for deviations from classic rationality (e.g., Simon 1956; Gabaix et al. 2006).

- Neuroscience: Investigation of how the brain balances accuracy and metabolic cost in representing the world (e.g., Levy & Baxter 2002; Niven & Laughlin 2008).

- Linguistics: Analysis of language as a system optimized for efficient communication (e.g., Hawkins 2004; Zaslavsky et al. 2018).

- Psychology: Recent incorporation of cognitive constraints into rational models (e.g., Griffiths et al. 2015).

This interdisciplinary approach highlights the synergy between structural constraints and functional principles in advancing our understanding of cognition.

Simon (1955; 1956) proposed that rational decision strategies must adapt to both the environmental structure and the cognitive limitations of the mind.

He introduced the concept of satisficing, where individuals use a heuristic to select the first option that meets a satisfactory threshold rather than searching for the optimal solution.Key Influence:

- This idea laid the foundation for the theory of ecological rationality, which argues that people adaptively use simple heuristics to exploit the structure of their natural environments.

- Notable contributions to this theory include works by Gigerenzer & Goldstein (1996), Gigerenzer & Selten (2002), Hertwig & Hoffrage (2013), and Todd & Gigerenzer (2012).

Simon’s framework emphasizes the interplay between cognitive constraints and environmental adaptation in shaping decision-making strategies.

Anderson's Rational Analysis

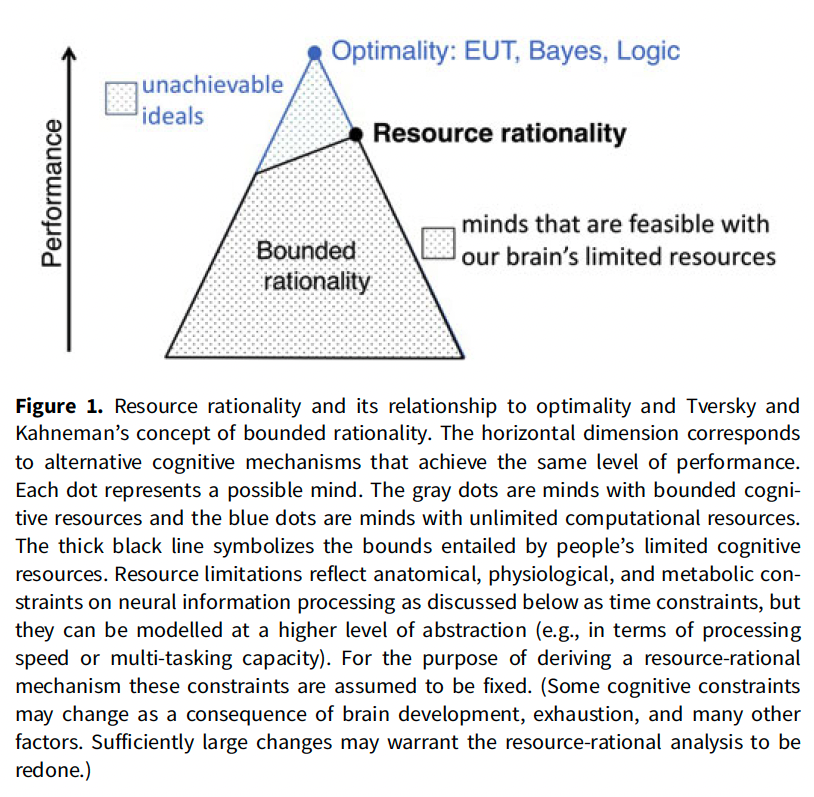

Anderson (1990) introduced rational analysis, a paradigm for understanding human cognition as a rational adaptation to environmental structures and goals. This approach derives models of human behavior based on environmental assumptions, bridging the computational level of analysis to the algorithmic level.

The principle of resource rationality allows researchers to construct rational process models that integrate functional assumptions with cognitive constraints. This has provided explanations for cognitive biases such as:

- Confirmation bias (Austerweil & Griffiths, 2011; Oaksford & Chater, 1994)

- Misconceptions of randomness (Griffiths & Tenenbaum, 2001)

- Gambler's fallacy (Hahn & Warren, 2009)

- Logical fallacies in argument construction (Hahn & Oaksford, 2007)

Rational analysis emphasizes that evolution has adapted the human mind to align with the structure of our evolutionary environment (Buss, 1995).

Six Steps of Rational Analysis:

- Precisely specify the goals of the cognitive system.

- Develop a formal model of the environment to which the system is adapted.

- Make minimal assumptions about computational limitations.

- Derive the optimal behavioral function based on steps 1-3.

- Examine empirical literature to confirm the predictions of the model.

- If predictions do not align, iterate the process.

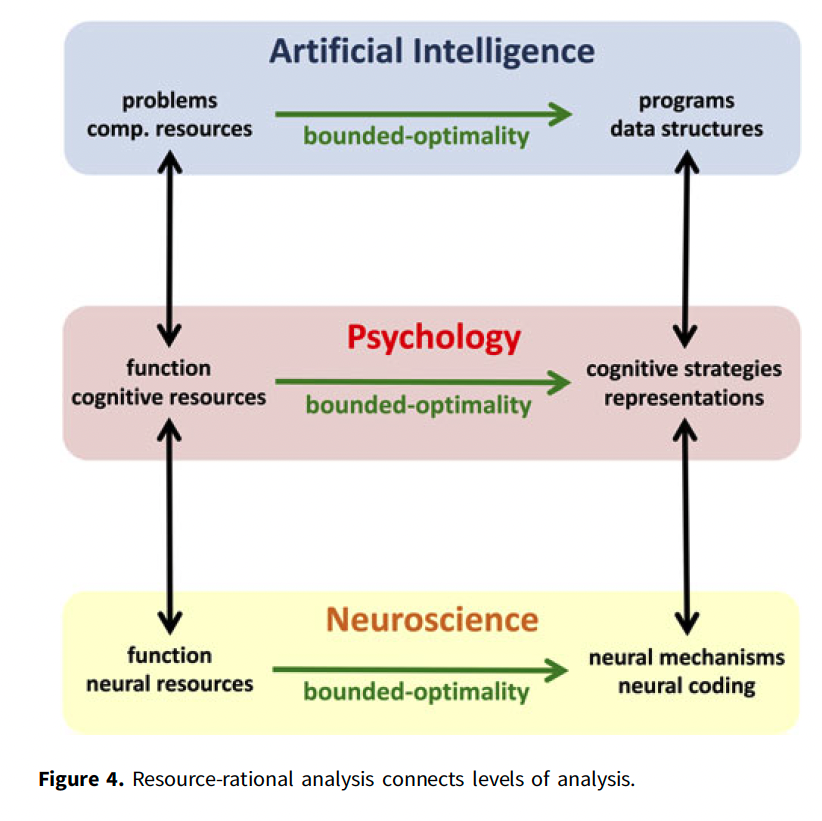

Theory of Bounded Optimality

AI researchers have developed a theory of rationality that addresses limited computational resources, known as bounded optimality (Horvitz, 1987; Russell, 1997). This theory designs optimal programs for agents with performance-limited hardware interacting with real-time environments.

A program is bounded-optimal for a given architecture if it allows the architecture to perform as well as or better than any other executable program. This idea has been applied to resource-bounded agents, like humans, to define how people can optimally use their finite time and cognitive resources (Griffiths et al., 2015; Lewis et al., 2014).

Key Takeaway: The concept of bounded rationality as a constrained optimization problem serves as a foundation for resource-rational analysis, a paradigm for modeling cognitive mechanisms and representations that synthesizes these ideas into a unified framework.

To express the principle of bounded optimality mathematically, the resource-rational mind ( m^* ) for a brain ( B ) interacting with the environment ( E ) is defined as:

\[m^* = \arg \max_{m \in M_B} \mathbb{E}_{P(T, l_T | E, A_t = m(l_t))} \left[ u(l_T) \right],\]where:

- $ M_B $: The set of biologically feasible minds.

- $ T $: The agent’s (unknown) lifetime.

- $ l_t = (S_0, S_1, \dots, S_t) $: The sequence of world states the agent has experienced until time $ t $.

- $ A_t = m(l_t) $: The action chosen by the mind $ m $ based on its life history $ l_t $.

- $ u(l_T) $: The utility function that assigns values to life histories $ l_T $.

Our theory assumes that the cognitive limitations inherent in the biologically feasible minds $ M_B $ include:

- A limited set of elementary operations (e.g., counting and memory recall are possible, but applying Bayes’ theorem is not).

- Limited processing speed (each operation requires a certain amount of time).

- Other constraints, such as limited working memory.

Critically, the world state $ S_t $ is constantly changing as the mind $ m $ deliberates. Therefore, a bounded optimal mind $ m^* $ must not only generate good decisions but must also do so quickly. Since each cognitive operation takes time, bounded optimality often necessitates computational frugality.

Explanation of the Two Formulas

1. Resource-Rational Heuristic for a Single Decision or Inference

The formula defines the resource-rational heuristic $ h^* (s_0, B, E) $, which represents the best heuristic $ h $ that a brain $ B $ can use in a given environment $ E $ and belief state $ s_0 $ for a single decision or inference:

\[h^*(s_0, B, E) = \arg \max_{h \in H_B} \left[ \mathbb{E}_{P(\text{result}|s_0, h, E, B)} \big[ u(\text{result}) \big] - \mathbb{E}_{t_h, \rho, \lambda | h, s_0, B, E} \big[ \text{cost}(t_h, \rho, \lambda) \big] \right],\]Where:

- $ H_B $: The set of heuristics executable by the brain $ B $.

- $ s_0 = (o, b_0) $: The observed state of the external world $ o $ and the initial belief state $ b_0 $.

- $ u(\text{result}) $: The utility of the result generated by the heuristic.

- $ \text{cost}(t_h, \rho, \lambda) $: The opportunity cost of applying the heuristic $ h $, which depends on:

- $ t_h $: Time required for execution.

- $ \rho $: Cognitive resources utilized.

- $ \lambda $: Opportunity cost per unit of resource and time.

This formula balances utility (accuracy of the result) with cost (time and resources) to select an optimal heuristic.

2. Boundedly Resource-Rational Heuristic with Limited Information

The second formula adjusts the first by considering limited information $ i $ about the environment $ E $, derived from direct experience, indirect experience, or evolutionary adaptation:

\[h^*(s_0, B, i) = \arg \max_{h \in H_B} \left[ \mathbb{E}_{E|i} \left[ \mathbb{E}_{P(\text{result}|s_0, h, E, B)} \big[ u(\text{result}) \big] \right] - \mathbb{E}_{t_h, \rho, \lambda | h, s_0, B, E} \big[ \text{cost}(t_h, \rho, \lambda) \big] \right].\]Key Differences:

- \(\mathbb{E}_{E \mid i}\) : An expectation over the possible environments $ E $ based on the limited information $ i $.

-

This accounts for uncertainty in the environment, relaxing the assumption that the agent has complete knowledge about $ E $.

- First Formula: Optimizes heuristic choice assuming full knowledge of the environment.

- Second Formula: Incorporates limited information about the environment, making it more realistic for real-world decision-making.

Both formulas highlight how resource-rational heuristics balance accuracy against cognitive and temporal costs in decision-making.

The Five Steps of Resource-Rational Analysis

Resource-rational analysis is a methodology for modeling cognitive mechanisms by balancing computational constraints and approximation accuracy. The process iteratively refines the model to align predictions with empirical evidence. Below are the five steps:

-

Define the Computational-Level Problem:

Formulate an aspect of cognition as a problem and its ideal solution at the computational level (functional description). -

Hypothesize the Computational Architecture:

Propose:- The class of algorithms that the brain might use to approximate the solution.

- The costs of computational resources required by these algorithms.

- The utility of achieving a more accurate solution.

-

Optimize the Algorithm:

Identify the algorithm within the proposed class that optimally trades off computational resources and approximation accuracy. This step uses formulas like Equation (3) or (4) to derive the optimal heuristic. -

Empirical Evaluation:

Test the predictions of the derived rational process model against empirical data to assess its validity. -

Refine and Iterate or Stop:

Address any significant discrepancies by:- Refining the computational-level theory (Step 1).

- Improving assumptions about the computational architecture and its constraints (Step 2).

- Deriving a more refined model.

Key Note:

The analysis can stop at Step 5 even if human performance deviates from predictions, as long as reasonable attempts have been made to model constraints based on available evidence.