Roles of Logical System

What are the basic principles for developing logic.

Logical Systems and Reasoning in LLMs

In this article, I attempt to answer the following questions:

- For what purpose are logical systems developed and advanced?

- What does it mean to say that LLMs do not have reasoning ability?

Brief History of Logic

The first developer of logic was Aristotle, who introduced syllogism (e.g., if $ A \rightarrow B $ and $ B \rightarrow C $, then $ A \rightarrow C $). Following this, propositional logic (PL) was developed, which uses propositions with binary truth values (true or false). This was the first logical system to define several key elements, including propositions, logical connectives, and implication rules (e.g., Modus Ponens). While PL provides a simple yet effective representation of truth values (e.g., “It is raining”), it fails to express more complex real-world statements, such as “There exists a town with humid weather.”

The next major classical logical system, First-Order Logic (FOL), introduced predicates and terms (constants, variables, and functions), along with formulae that play a role similar to propositions in propositional logic. Although FOL provides a natural extension to higher-order logic, it remains insufficient for representing truth values in real-world contexts. For example:

- PL and FOL are monotonic, whereas the real world includes non-monotonic truth values—meaning that the evaluation of propositions or sentences can change over time. However, classical logical systems cannot represent such changes.

- The real world includes uncertainty in both truth values and inference. However, PL and FOL do not account for uncertainty or vagueness in reasoning.

Due to these limitations, subsequent research has focused on developing more expressive and efficient logical systems to better handle truth values in real-world scenarios. We do not go deeper on advanced design on logical system and provide list of them in Appendix.

Fundamental Roles of Logic

| Function | Objective | Mathematical Formulation |

|---|---|---|

| 0. Given | Knowledge and inference rules | \(\Gamma, \Delta, \varphi, P\) |

| 1. Truth Evaluation | Determine whether a given sentence is true | \(\Gamma \models \varphi\) |

| 2. Consistency Checking | Ensure no contradictions in premises | \(\neg (\Gamma \vdash P \land \Gamma \vdash \neg P)\) |

| 3. Validity Checking | Verify whether the conclusion logically follows | \((\Gamma \vdash \varphi) \Rightarrow (\Gamma \models \varphi)\) |

| 4. Goal-Directed Reasoning | Add assumptions to the premises to infer a desired sentence | \(\Gamma \cup \Delta \vdash \varphi\) |

| 5. Knowledge Representation | Express relationships between entities in a world | \(K = \{ (E, R) \}\) |

| 6. Non-Monotonic Reasoning | Evaluate sentences whose truth values change with additional assumptions | \(\Gamma \vdash \varphi, \Gamma \cup \Delta \not\vdash \varphi\) |

| 7. Inference & Knowledge Derivation | Derive new knowledge from premises | \(\Gamma \vdash \varphi\) |

| 8. Expressiveness | Measure the range of concepts that can be expressed | \(L_1 \succ L_2 \iff \forall \varphi \in L_2, \varphi \in L_1 \text{ but } \exists \psi \in L_1, \psi \notin L_2\) |

| 9. Computability | Determine whether logical operations can be computed | \(L \text{ is Turing-complete} \iff \forall f: \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}, \exists \varphi \in L, \text{ such that } \varphi \text{ computes } f\) |

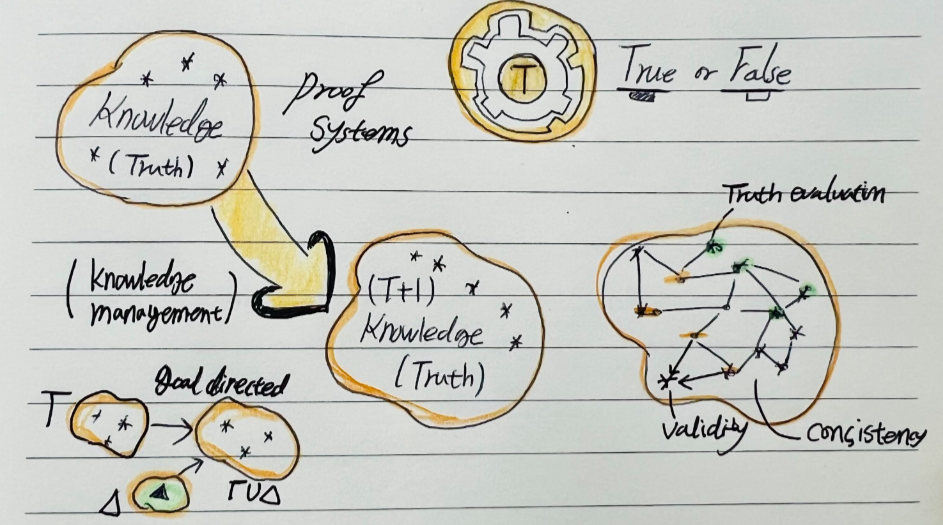

Logical systems consist of two fundamental components [L0]:

- Knowledge, which includes premises, assumptions, and axioms.

- Inference rules, which define how knowledge elements are connected and manipulated to evaluate truth values.

These two components assume that knowledge within a given system can be evaluated in terms of truth values [1], which may not necessarily be binary (true/false) but could follow a broader spectrum, such as degrees of truth (e.g., fuzzy logic). This concept is similar to theory formulation in scientific research, where researchers propose hypotheses, assumptions, and conjectures to determine what is correct. In this process, inference rules are applied to premises to ensure logical correctness.

To understand the necessity of inference rules, we must acknowledge that our premises ( \Gamma ) and possibly upcoming premises ( \Delta ) are inherently imperfect. They may contain contradictions, and even the truth evaluation of existing ( \Gamma ) may be false in some underlying possible worlds [2,3]. Thus, managing knowledge requires determining which premises are true and false within a logical system. Another crucial function is guiding premises toward a desired conclusion, which is conceptually similar to goal-conditioned reinforcement learning [4]. For instance, we can pose a query:

“How do we make ( P = T ) within the premises if ( P = F ) initially?”

This question asks what assumptions ( \Delta ) must be introduced to achieve a desired premises via non-monotonic reasoning [6]. One might also seek the minimal set ( \Delta ) that efficiently transitions the premises. A key advantage of logical systems is that they provide a structured and consistent framework for knowledge representation [6]. Within this system, correctness can be verified without additional resources, ensuring that knowledge remains well-organized. In contrast, unstructured systems—where premises are added without clear rules—fail to guarantee consistency in truth values. A structured logical system ensures incremental and safe inference generation [7]. However, as the number of premises grows, efficiently evaluating consistency becomes increasingly difficult—this is known as the Frame Problem. Solving this requires more structured and optimized logical systems [8,9].

Conclusion

Handling truth values in the real world is a fundamental challenge in formal reasoning, error minimization, and assumption-based inference. A logical system provides a framework for managing truth-value-based knowledge, ensuring that inference rules guide reasoning correctly. Moreover, logical frameworks allow verification of complex reasoning steps, even for advanced inference models such as default logic. By structuring reasoning step by step, logical systems ensure correctness and provide explainability in reasoning, making inference processes transparent and interpretable.

Do LLMs Have Reasoning Ability?

1. Do LLMs Have Knowledge Premises?

A: Somehow, but No.

LLMs possess implicit knowledge encoded within their vast parameters. This knowledge is stored in a way similar to key-value memories, where word embeddings capture relationships between concepts. However, unlike formal logical premises, this knowledge is distributed and statistically inferred rather than explicitly structured.

2. Do LLMs Have Inference Rules?

A: Clearly No.

LLMs do not inherently follow explicit inference rules as formal logical systems do. While some attention heads might capture patterns that resemble certain inference mechanisms, these are not explicitly defined nor sufficiently expressive to guarantee consistent logical inference. Their reasoning is emergent and heuristic, rather than rule-based.

3. Can LLMs Perform Long-Chain Reasoning?

A: Clearly No.

In a structured logical system, a long chain of reasoning requires consistency of premises, correctness of inference steps, and logical soundness. LLMs, however, cannot guarantee consistency in their conclusions, nor can they verify whether their reasoning process adheres to formal logical constraints. They often exhibit hallucinations and spurious correlations, which are signs of pattern-based generalization rather than rigorous reasoning.

4. Could LLMs Contain Embedded Reasoning?

A: Almost No.

One possible way to argue that LLMs possess reasoning ability is by conjecturing:

“All knowledge and inference rules are implicitly encoded within the model’s parameters, and they could be extracted when needed.”

However, I find this impractical and infeasible. Even if inference rules were embedded in parameters, extracting them is not a formalized process because LLMs are highly sensitive to prompts and do not consistently retrieve information in a structured, rule-based manner.

5. Can We Inject Knowledge and Inference Rules via Distribution Matching?

A: Almost No.

A natural question arises:

“Can we inject explicit knowledge and inference rules into LLMs by aligning their distributions with a structured logical system?”

While this idea is theoretically interesting, it is an extremely difficult problem in distributed representation systems. The main challenge is that inference rules in formal logic are discrete and symbolic, whereas the internal representations of LLMs are continuous and high-dimensional.

- Mapping discrete rules into continuous vector spaces introduces a fundamental gap, as formal logic requires exact reasoning steps, while neural networks operate via soft constraints and approximations.

- Compositionality in reasoning is also difficult to enforce in LLMs, since they rely on pattern recognition rather than rule-based inference. Even if a model can approximate certain reasoning behaviors, ensuring systematic generalization across logical structures remains an open challenge.

Conclusion: Do LLMs Truly Reason?

A: Almost No.

LLMs do not possess true reasoning ability in the formal logical sense. Instead, they operate as probabilistic pattern recognizers, relying on vast amounts of memorized relational knowledge and learned statistical correlations. While they can generate responses that mimic reasoning, they lack the ability to verify, correct, or consistently derive conclusions through explicit logical steps.

Even if we consider injecting structured knowledge through distribution matching, the symbolic-to-continuous gap in representation makes it an impractical and infeasible solution. In essence, LLMs’ “reasoning” is an emergent phenomenon of large-scale pattern recognition, rather than a structured logical process.

Appendix

| Logic Type | Description & Purpose | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Default Logic | Allows reasoning with default assumptions when explicit knowledge is missing. Common in AI and expert systems. | Reiter (1980) |

| Default Reasoning (Poole) | A probabilistic extension of default logic that incorporates uncertainty in assumptions. | Poole (1988) |

| Independent Choice Logic | Models independent decisions in a probabilistic framework, useful for decision-making and game theory. | Poole (1997) |

| Modal Logic | Introduces necessity (□) and possibility (◇) operators, allowing reasoning about possibility, necessity, and obligations. | Kripke (1963) |

| Epistemic Logic | A modal logic focused on knowledge representation in multi-agent systems. | Hintikka (1962) |

| Doxastic Logic | Similar to epistemic logic but focuses on reasoning about beliefs rather than knowledge. | Konolige (1986) |

| Temporal Logic | Extends logic to include time-based reasoning, used in software and hardware verification. | Prior (1967) |

| Fuzzy Logic | Allows truth values between 0 and 1, enabling reasoning under vagueness and imprecision. | Zadeh (1965) |

| Probabilistic Logic | Integrates probability theory with logic to handle uncertainty. | Nilsson (1986) |

| Bayesian Logic | Uses Bayesian networks to model probabilistic inference. | Pearl (1988) |

| Paraconsistent Logic | Handles contradictions without collapsing into triviality. Useful in AI and philosophy. | da Costa (1974) |

| Relevance Logic | Ensures logical relevance in implication, avoiding paradoxes of classical logic. | Anderson & Belnap (1975) |

| Intuitionistic Logic | Rejects the law of the excluded middle, emphasizing constructive proof methods. | Heyting (1930) |

| Higher-Order Logic (HOL) | Extends first-order logic to allow quantification over predicates and functions. | Church (1940) |

| Multi-Valued Logic | Expands beyond binary logic with multiple truth values (e.g., ternary, Łukasiewicz logic). | Łukasiewicz (1920) |

| Many-Worlds Semantics | A framework for reasoning about multiple possible worlds, useful in AI and philosophy. | Lewis (1973) |

| Defeasible Logic | A non-monotonic logic where conclusions can be overridden by stronger evidence. | Nute (1994) |

| Argumentation Logic | Models structured argumentation and conflict resolution in reasoning systems. | Dung (1995) |

| Description Logic | The formal foundation for ontologies and the Semantic Web. | Baader et al. (2003) |

| Linear Logic | Models resource-sensitive reasoning, used in computational logic and type theory. | Girard (1987) |

| Hybrid Logic | Combines modal and first-order logic for enhanced expressiveness. | Blackburn (1993) |

| Causal Logic | Introduces causality into logical reasoning, important in AI and philosophy of science. | Pearl (2000) |

Application Roles of Logic

N/A - I will write this part after learning more about logical systems.