Argumetation Framework

Dung’s Argumentation Framework (AF)—introduced in 1995 by Phan Minh Dung—was developed to formalize the inherently imperfect and dynamic nature of human controversies. AF models each argument as a node and represents attack relations as edges, shifting the focus from the question of “what is true?” to the question of “what can remain undefeated?” In other words, the framework centers on the stability of arguments rather than their truth value.

Humans naturally try to maintain coherence within their belief systems by minimizing internal contradictions and responding to external challenges. AF abstracts precisely this defensive and structural aspect of human thinking into mathematical form. Because it evaluates arguments solely through attack and defense relations—without considering their content or factual accuracy — AF is an extremely minimalistic model; yet, its simplicity allows it to capture essential patterns in human argumentative behavior.

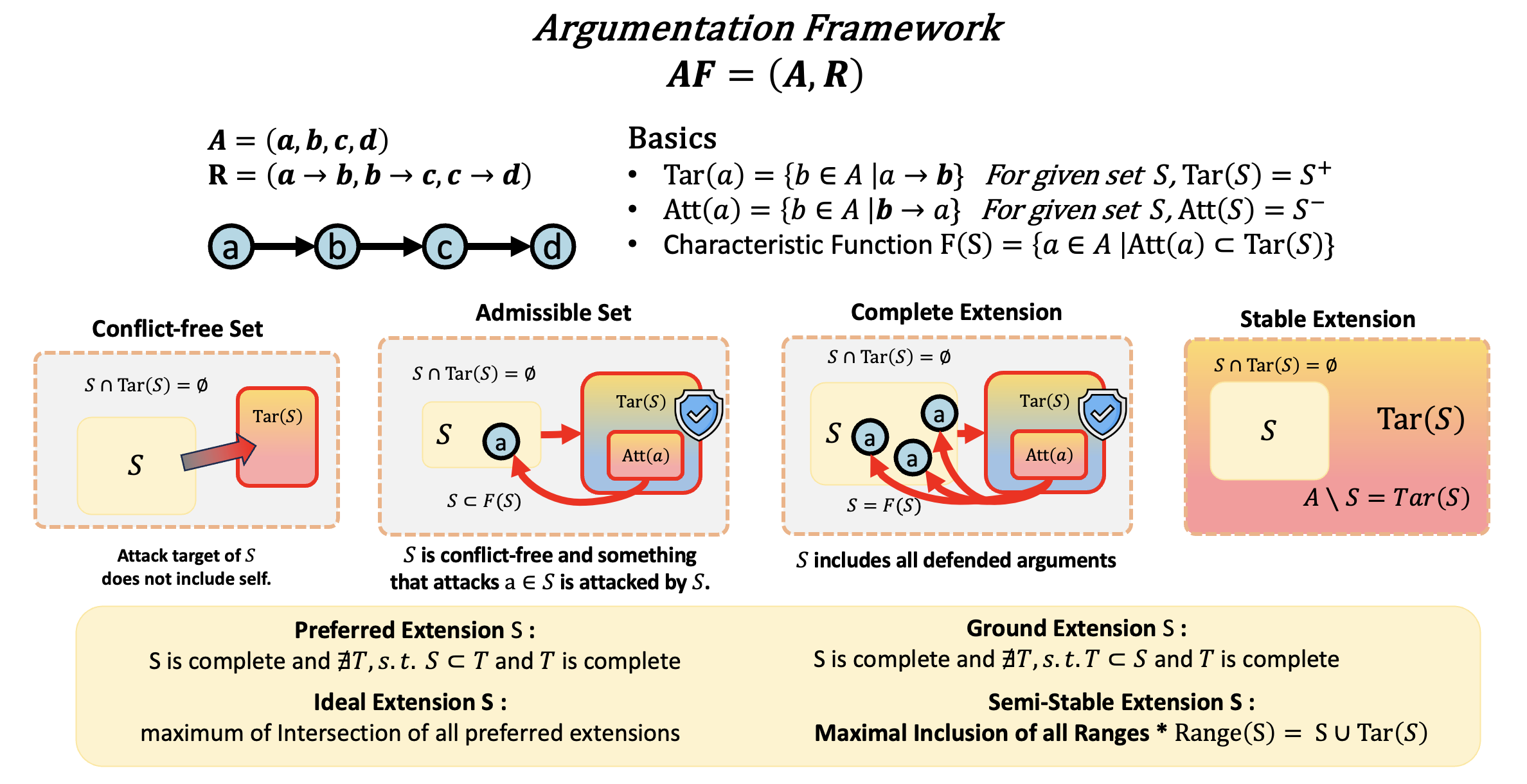

Semantic Set Types: Admissible, Conflict-free, Complete, Stable

Core concepts in AF include conflict-free, admissible, complete, and stable sets of arguments.

- A conflict-free set contains no mutually attacking arguments.

- An admissible set not only avoids internal conflict but also defends itself against external attacks.

- A complete extension is an admissible set that additionally includes all arguments capable of defending it.

- A stable extension goes even further: it requires the set to attack every argument outside it.

$S$ is stable if $$ S \cap \mathrm{Tar}(S) = \varnothing \qquad\text{and}\qquad A \setminus S = \mathrm{Tar}(S). $$ See the more definitions in Overleaf

Although stable extensions are theoretically elegant, they rarely correspond to actual human belief systems or dialogues, because they represent an extreme form of argumentative dominance—akin to a closed mindset that rejects everything outside itself. In fact, stable extensions can resemble cognitive rigidity or political extremism more closely than balanced reasoning.

The real difficulty with AF, however, does not lie in its static structure but in its inability to account for the semantic shifts that occur when arguments are introduced dynamically or in a particular order. Human dialogue is inherently dynamic: new pieces of evidence arise, new attack relations are formed, and the meaning of existing arguments can shift depending on context. Yet Dung’s AF has no way to represent temporal order. Arguments simply “exist” in the framework, and whether they were introduced earlier or later is irrelevant to the model. In actual conversations, however, later arguments often appear more forceful—not because they are intrinsically stronger, but because they carry an implicit tag of being crafted in direct response to a preceding claim. Humans tend to evaluate the intent and immediacy of a counterargument more heavily than its raw logical strength. This “advantage of the later mover” is absent from AF’s representational vocabulary but is a crucial psychological factor in real argumentative exchanges.

A more serious issue arises when new arguments or new attack relations are introduced into an existing AF. When this happens, the entire extension structure may need to be recalculated from scratch. A single additional argument can invalidate an admissible set or overturn a stable one. Moreover, although attacks appear local—one argument attacking another—their semantic effects are global. If a new argument B attacks an argument A, all arguments dependent on A, directly or indirectly, become destabilized, and any extension that included A may collapse. A similar phenomenon occurs in human reasoning: refuting a central belief can unravel many connected beliefs and disrupt the coherence of an entire belief system.

Mutual attacks, where two arguments attack each other, reveal another ambiguity in AF. In such cases, AF can only register symmetric rejection; it cannot determine which argument is more persuasive. In real dialogue, however, the argument introduced later often appears more credible because it is framed as a direct rebuttal. AF cannot capture this context-dependent asymmetry, as it focuses solely on structural relations. It lacks the representational resources to encode questions like “Which argument is more trustworthy in this context?” or “Which one better addresses the opponent’s reasoning?” For this reason, AF provides only a minimal model of argumentative interaction, and subsequent extensions have attempted to incorporate temporal ordering, priorities, degrees of support, or weighted attacks to more faithfully reflect the complexity of human reasoning.

In summary, AF provides a vital abstract skeleton for understanding human reasoning. Patterns of attack and defense, mechanisms of conflict resolution, and the structural stability of belief systems all align with AF’s conceptual structure. However, actual human reasoning is fundamentally dynamic, sensitive to temporal order, and entwined with semantic, psychological, and social dimensions. AF is a static snapshot, while human thought is a continuously evolving system. Understanding this gap remains a central challenge not only in argumentation theory and cognitive science but also in contemporary research on reasoning in large language models.

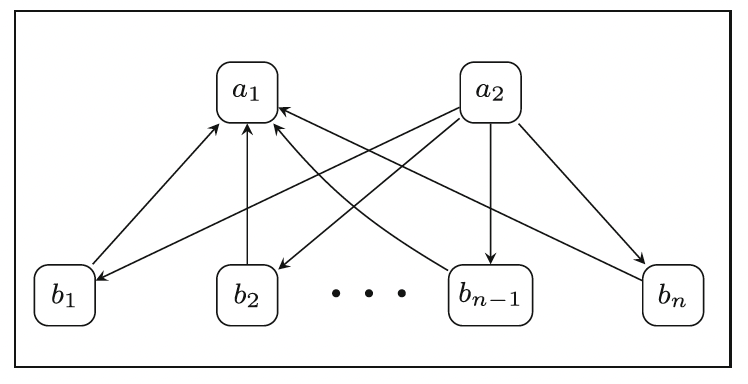

Assumption-Based Argumentation (ABA)

Assumption-Based Argumentation (ABA) is a structured argumentation framework that extends Dung’s abstract argumentation by providing explicit internal structure for how arguments are generated and how attacks arise. While Dung’s framework represents arguments as abstract nodes connected by attack relations, ABA offers a rule-based mechanism that explains why arguments attack each other, grounding the abstract attack relation in the logical structure of the arguments themselves.

Formally, an ABA framework is defined as a tuple $\mathcal{F} = \langle \mathcal{L}, \mathcal{R}, \mathcal{A}, \overline{\cdot} \rangle$, where $\mathcal{L}$ is a formal language, $\mathcal{R}$ is a set of inference rules of the form $\alpha \leftarrow \beta_1, \ldots, \beta_n$, $\mathcal{A} \subseteq \mathcal{L}$ is a designated set of assumptions, and $\overline{\cdot}$ is a contrary mapping assigning to each assumption its contrary, representing what counts as a direct rejection of that assumption.

Arguments in ABA are constructed from these rules and assumptions. An argument is typically represented as a pair $(\Delta, c)$, where $\Delta \subseteq \mathcal{A}$ is the set of assumptions forming the support of the argument, and $c \in \mathcal{L}$ is the conclusion derived from $\Delta$ using rules in $\mathcal{R}$.

A key characteristic of ABA is how attack is defined. Rather than defining attack as a conflict between the conclusions of two arguments, ABA grounds attack in a structural relationship between arguments and their underlying assumptions. An argument $A$ attacks another argument $B$ if and only if:

\[\exists a \in \text{Supp}(B) \text{ such that } A \vdash \overline{a}.\]In other words, attack occurs when the conclusion of one argument derives the contrary of an assumption on which another argument depends. Because an argument collapses if any of its assumptions is defeated, this contrary-based attack notion captures how arguments undermine each other at the level of foundational commitments rather than solely through claim-level contradictions.

Through this mechanism, ABA provides a bridge between abstract argumentation and nonmonotonic rule-based reasoning. It naturally represents defaults, exceptions, and context-dependent knowledge by treating assumptions as defeasible components and by identifying their contraries as explicit points of conflict. This structured perspective produces richer explanations for why arguments defeat each other and forms the basis for further extensions such as ABA⁺, which incorporates preferences among assumptions to determine which attacks ultimately succeed.

ABA + : Augment Preferences

Although Dung introduced the abstract notion of argumentation in 1995, the move from abstract nodes to fully structured arguments was crystallized through the work of Francesca Toni and collaborators. Toni played the central role in transforming Assumption-Based Argumentation (ABA) into a systematic formalism grounded in rule-based reasoning. Her formulation defined ABA using a clear tuple structure — a formal language, a set of inference rules, a distinguished set of defeasible assumptions, and a contrary mapping — and demonstrated how arguments are constructed from these components through deductive derivations.

Crucially, Toni’s work established how attacks emerge within this structured setting: an argument attacks another by deriving the contrary of one of its underlying assumptions. This provided a logical foundation for Dung’s abstract attack relation, linking it to the internal mechanisms of rule-based inference. Through this systematization, ABA became a powerful unifying framework capable of expressing a wide spectrum of nonmonotonic reasoning phenomena, including default reasoning, exceptions, and logic programming semantics.

Subsequent developments, most notably ABA+, extend this foundation by integrating preferences directly into the attack relation. Rather than remaining at a meta-level, preferences in ABA+ determine when an attack succeeds or reverses, shaping the dynamics of conflict in a principled way. In this sense, ABA+ and later structured-argumentation frameworks are natural continuations of Toni’s original formulation, preserving its core logical architecture while enriching it to capture more realistic, prioritized forms of reasoning.

Assumption-Based Argumentation with Preferences (ABA+) is a principled extension of the classical ABA framework that incorporates explicit preference information directly into the attack relation. An ABA+ framework is defined as a tuple $(L, R, A, \bar{\cdot}, \leq)$, where $(L, R, A, \bar{\cdot})$ is the standard ABA structure consisting of a language, a set of inference rules, a set of assumptions, and a contrary mapping. The additional component $\leq$ is a transitive preference ordering over assumptions, representing their relative reliability or priority. Unlike approaches that treat preferences as an external filter, ABA+ embeds preferences into the attack mechanism itself. In ABA+, a set of assumptions $A$ attacks a set $B$ only if $A$ derives the contrary of some $\beta \in B$ without relying on assumptions that are strictly less preferred than $\beta$. If a derivation depends on assumptions that are less preferred than the target, the attack does not succeed; instead, the attack is reversed so that $B$ attacks $A$. This attack-reversal mechanism ensures that lower-priority assumptions cannot undermine higher-priority ones while preserving the structured nature of ABA reasoning.

The semantics of ABA+ follow the classical ABA and Dung-style structure but evaluate conflict and defense using the preference-aware attack relation. A set of assumptions is conflict-free if it does not attack itself under these preference conditions, and it is admissible when it is closed, conflict-free, and capable of defending itself against all attacks. Preferred, stable, complete, grounded (well-founded), and ideal extensions are defined in the usual way but with respect to the preference-sensitive notion of attack. Importantly, ABA+ is a conservative extension of ABA: when the preference ordering is empty, all attacks reduce to classical ABA attacks, and all ABA+ semantics coincide exactly with their ABA counterparts.

ABA+ satisfies several desirable structural and rationality properties. Conflict preservation ensures that no extension can contain assumptions that attack each other in the underlying ABA framework. The empty-preference principle guarantees that ABA+ behaves identically to ABA when preferences are absent. Moreover, when maximally preferred assumptions form a closed and conflict-free set, that set is included in all complete, stable, and grounded extensions, ensuring high-priority information persists across all acceptable viewpoints. ABA+ also satisfies essential rationality postulates: its extensions are deductively closed and avoid both direct and indirect inconsistencies.

A major theoretical innovation of ABA+ is the introduction of Weak Contraposition, a relaxed version of contraposition that applies only when an attack involves assumptions that are less preferred than the target. When an ABA+ framework is flat and satisfies Weak Contraposition, it enjoys strong guarantees including the existence of complete extensions, the Fundamental Lemma, and uniqueness of grounded and ideal extensions. These results parallel those of flat ABA while preserving the influence of preferences. Overall, ABA+ provides a robust and expressive formalism for prioritized reasoning, integrating preferences into the core attack relation in a transparent and semantically grounded manner.

Weak Contraposition.

Imagine a school in which students have different levels of credibility.

Let $\beta$ be a highly trusted student, while $\gamma$ is less trusted ($\gamma < \beta$).

Suppose a group of students $E$ files a complaint against $\beta$, but the complaint relies on $\gamma$’s testimony.

Since $\gamma$ is less credible than $\beta$, the complaint cannot succeed.Weak Contraposition captures the idea that:

If an attack on a more credible student ($\beta$) depends on a less credible one ($\gamma$),

then the framework must also allow a justified complaint against $\gamma$

supported by students who are at least as credible as $\beta$.A framework satisfies Weak Contraposition if:

\[E \vdash \bar{\beta} \quad\text{and}\quad \exists \gamma \in E \ \text{such that} \ \gamma < \beta\]imply that there exists a set of assumptions $E’$ such that

\[E' \vdash \bar{\gamma} \quad\text{and}\quad \forall \delta \in E',\; \beta \le \delta .\]In words: whenever a derivation of $\bar{\beta}$ uses an assumption $\gamma$ strictly less preferred than $\beta$, the system must also allow a derivation of $\bar{\gamma}$ using only assumptions that are at least as preferred as $\beta$.

Knowledge Conflict: AF, Belief Revision, and Default Logic

Intelligent systems—whether symbolic reasoning engines or modern large language models (LLMs)—must constantly manage knowledge conflicts. As new information arrives, it can contradict, override, or refine previously held beliefs. Although the observable outcome often appears simple (“the system updates its knowledge”), the underlying reasoning principles differ dramatically depending on the theoretical framework used to interpret the conflict.

Knowledge conflicts do not arise from a single source. They may emerge from:

- Argument-level incompatibility (e.g., contradictory claims or premises),

- Preference-level competition (e.g., newer or more reliable information dominating older beliefs), or

- Justification-level failure (e.g., default rules losing support when their conditions no longer hold).

Because these conflicts originate from different mechanisms, each reasoning paradigm provides its own method for resolving them. As a result, knowledge conflict is best understood not as one phenomenon but as a set of philosophically distinct processes that converge only at the level of observable behavior.

This document proposes a unified perspective on these processes, articulating how different Non-Monotonic Reasoning (NMR) frameworks—argumentation-based, preference-based, and justification-based—approach knowledge conflicts, why they update differently, and how these distinctions apply to LLM reasoning.

2.1 Argument-Based Conflict

Argumentation frameworks (e.g., Dung AF, ABA, ASPIC+) treat conflicts as attacks between arguments. Two arguments cannot both be accepted if one invalidates the other’s claim, premise, or assumption. A contradiction (e.g., “A is president in 2020” vs. “B is president in 2021”) is represented as an attack relation.

- Conflict origin: relational incompatibility

- Conflict type: argument-level conflict

- System question: “Which argument defeats the other?”

This framework emphasizes defeat, defense, and extension semantics (admissible, complete, stable sets).

2.2 Preference-Based Conflict

Belief revision models (AGM, preference-based AF, ranking-based selection) treat conflicts as a problem of competing priorities.

Newer, stronger, or more reliable information may outrank older or weaker information. Thus, a conflict is solved by choosing the preferred belief.

- Conflict origin: priority ordering

- Conflict type: belief-level conflict

- System question: “Which belief do we trust more?”

Here, representation focuses on weights, credibility measures, and selection functions.

2.3 Justification-Based Conflict

Default logic and Truth Maintenance Systems (TMS) use justifications to express assumptions that remain valid unless contradicted.

When new information arrives that falsifies a justification (e.g., “the president has changed”), the corresponding default world collapses, and an alternative branch becomes active.

- Conflict origin: conditional assumption failure

- Conflict type: branch-level conflict

- System question: “Which world’s justifications remain stable?”

Updates take the form of branch collapse, dependency reevaluation, and default override.

3. Why These Frameworks Behave Differently

Though all frameworks ultimately select the updated knowledge, their internal reasoning differs because the cause of the conflict differs.

- Argumentation resolves conflicts via attack/defense semantics.

- Belief revision resolves them via preference ordering and selection.

- Default logic resolves them via justification checking and branch reconfiguration.

Thus, even when the answer is identical (e.g., “Biden is president”), the reasoning behind the update is entirely different.

4. Knowledge Maintenance and Representational Costs

Storing knowledge symbolically enables incremental updates and the preservation of global consistency. However, each framework requires:

- different representational capacities,

- different maintenance operations, and

- different computational costs.

The following table summarizes the differences:

| Framework | Representation Required | Maintenance Operation | Computational Cost | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argumentation-Based | Arguments, attack relations | Recomputing extensions (admissible, etc.) | Low–Medium | Clear conflict modeling, simple structure | Cannot represent defaults, context, or justification explicitly |

| Preference-Based | Beliefs + preference/credibility ordering | Re-ranking, selection, coherence checks | Medium | Handles reliability & recency well | Cannot express branch structures or conditional assumptions |

| Justification-Based | Default rules, justifications, branch structure | Checking justification validity; branch collapse | Medium–High | Models exceptions, context, evolution | High complexity, justification explosion, branching overhead |

Although all frameworks eventually converge on the same observable outcome (e.g., updating to the correct fact such as “Biden is president”), they differ profoundly in what they consider important:

- Argumentation cares about who defeats whom.

- Preference-based models care about which belief is stronger.

- Justification-based systems care about whether the conditions for a default remain stable.

These deeper architectural differences determine:

- how knowledge is stored,

- how conflicts are detected,

- how revisions occur,

- and how stable the reasoning process remains across time and context.

A unified treatment of knowledge conflict must recognize these distinctions and integrate them into a broader account of how knowledge evolves.

AF Does Not Handle: Knowledge Evolution

The Knowledge Evolution Problem concerns how an intelligent system maintains a coherent and up-to-date understanding of the world as new information arrives and as the context in which knowledge is applied changes. A knowledge state is not static; it continuously shifts in response to incoming evidence, changes in time or location, updated norms, or new conceptual interpretations. The central challenge is determining what should remain stable and what should be revised as circumstances evolve. This requires a structured way to represent what the system assumes by default, what conditions allow those assumptions to remain valid, and how exceptions or new facts should trigger changes.

At the core of this process are default assumptions. These are statements the system treats as true unless there is a reason to doubt them. Defaults can arise from statistical regularities (“birds usually fly”), conceptual expectations (“a president refers to a single individual”), normative rules (“unless specified otherwise, the meeting proceeds”), or the learned distributional priors of models such as LLMs. Defaults carry the system’s baseline expectations about the world and make reasoning efficient because they eliminate the need to reevaluate every claim from scratch.

However, defaults cannot be applied blindly. They require justifications—conditions that make it reasonable to rely on the default in the current situation. A justification captures the idea of “this assumption holds as long as nothing contradicts it.” For example, one assumes that a president remains the same unless an election has occurred; one assumes a restaurant is open unless it is unusually late; one assumes a person is healthy unless signs of illness appear. Justifications are therefore the stabilizing force behind defaults. They indicate when the default is safe and when it is fragile. As long as a justification remains consistent with the system’s knowledge and context, the default holds.

Knowledge must evolve when a justification breaks. This may happen because of a direct contradiction (“Biden, not Trump, is now president”), a stronger and more reliable piece of evidence, a shift in relevant context (time, location, or domain), or a growing accumulation of weak signals that makes the default less plausible. When this happens, the system effectively “switches defaults”: it stops treating the old assumption as baseline and promotes a new assumption to default status. This switching is not simply a conflict resolution step—it reflects a deeper commitment to stability. The system abandons one worldview and adopts another because the underlying conditions that supported the earlier view are no longer valid.

A crucial aspect of the Knowledge Evolution Problem is that context plays a central role. Knowledge is partly invariant (facts that remain true across all contexts) and partly variant (facts that depend on time, place, or conditions). An intelligent system cannot create a separate world for every possible context; instead, it maintains a shared core of stable knowledge while allowing only context-sensitive pieces to vary. This leads to a structure where most knowledge is consistent across contexts, and only specific elements change when context features—such as time or norms—shift. This is fundamentally different from attack-based argumentation models, which focus on conflict rather than stability, and lack a way to represent what the system should assume by default or how knowledge should persist across contexts.

In summary, knowledge evolution involves three interconnected processes: (1) Setting defaults, which define the system’s baseline expectations; (2) Maintaining justifications, which ensure that those defaults remain valid in the current context; and (3) Switching defaults, which replaces one baseline belief with another when the justification for the original belief no longer holds.

These mechanisms together allow a reasoning system to be both stable and adaptive. Stability comes from the persistence of defaults across contexts; adaptability comes from the ability to abandon those defaults when the world or context changes. Understanding and designing these mechanisms is essential for any system—symbolic or neural—that aims to maintain coherent knowledge over time.

Reference

[1] Dung, Phan Minh. “On the acceptability of arguments and its fundamental role in nonmonotonic reasoning, logic programming and n-person games.” Artificial intelligence 77.2 (1995): 321-357.

[2] Dung, Phan Minh, Robert A. Kowalski, and Francesca Toni. “Assumption-based argumentation.” Argumentation in artificial intelligence. Boston, MA: Springer US, 2009. 199-218.

[3] Čyras, Kristijonas, et al. “Argumentative XAI: a survey.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.11266 (2021).

[4] Atkinson, Katie, et al. “Towards artificial argumentation.” AI magazine 38.3 (2017): 25-36.

[5] Croitoru, Cosmina, and Madalina Croitoru. “Indepth combinatorial analysis of admissible sets for abstract argumentation.” Annals of Mathematics and Artificial Intelligence 90.11 (2022): 1139-1158.

[6] Bondarenko, Andrei, et al. “An abstract, argumentation-theoretic approach to default reasoning.” Artificial intelligence 93.1-2 (1997): 63-101.

[7] Čyras, Kristijonas, and Francesca Toni. “ABA+ assumption-based argumentation with preferences.” Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Conference on Principles of Knowledge Representation and Reasoning. 2016.